Jyväskylä University—Meeting with 40 graduate students in the music department at Jyväskylä, Finland, we’re talking about noise: the kind, entropic kind, that helps you tune in, get centered. Waves at the ocean, water in a brook. By now over a dozen publications draw the paradoxical conclusion that a certain amount of noise improves brain performance, signal detection. This research bears out the predictions of stochastic resonance, the only theory to have come to neuroscience by way of meterology.

Jyväskylä University—Meeting with 40 graduate students in the music department at Jyväskylä, Finland, we’re talking about noise: the kind, entropic kind, that helps you tune in, get centered. Waves at the ocean, water in a brook. By now over a dozen publications draw the paradoxical conclusion that a certain amount of noise improves brain performance, signal detection. This research bears out the predictions of stochastic resonance, the only theory to have come to neuroscience by way of meterology.

A hand shoots up. Great! I live for curiosity, its humble courage. “Are you talking about pink noise, or white noise?” I dunno. Wiseacre.

“The future is already here–it’s just not evenly distributed”–William Gibson, cyberpunk novelist. And there’s a lot of it in Finland.

I rode up to Jyväskylä in the pet car. The dogs were very well behaved.

Jyväskylä University is one of the few Music Therapy capitals in the cacophonous world of biomedicine, and in this market, I’m going long on music therapy. Not only do they have sophisticated graduate students who are way ahead of me, they’ve got toys: magneto-encephalography, functional MRI, EEG, motion lab.

Of course there are different kinds of noise—I’m still sorting that out. But I know that in the right measure, noise means variability, joy, a sense of humor, childlike innocence, naïveté, clowning, health. It’s how I know you’re really there.

Before you were born, the obstetricians studied the variability of your heart rate—that’s good noise. Monotony, by contrast, connotes stern-ness, joylessness, illness. Horror movies use this rhythmic principle a lot–think of the theme music of classics like Jaws, Hitchcock films.

To Jyväskylä I imagine I’ve brought a little chunk of the future. A speculation, the timorous lovechild of my courage and my vanity: it’s the noise, the randomness in music, that improves self-knowledge, by helping us out with a royal signal detection problem–interoception. Interoception is bodily awareness, like the ability to sense your own heart beat, your breathing. Interoception links in turn to empathy: how can you “feel for” another being if you cannot feel your self? To tune up your interoception, to be present, admit some noise, the underwriter to silence, that golden child who’s always pointing towards the future. A little chatter, a little static in the back. Helps you think.

The hotel offers a jazz ballad on the overhead speakers. Leaning in on a long flat note, the trumpet just crossed over to self pity. Music evokes pre-history, childhood memories, and now, pre-adolescent whining. At the front desk, they loan me a bicycle with disc brakes, and an automatic transmission. (Do we have these back home? Am I in the future?) I take the helmet—a cycling neurologist without one is a jarring sight—and find the museum of Central Finland, which says that history is pretty new around here: the pre-historic age didn’t end here until 1500.

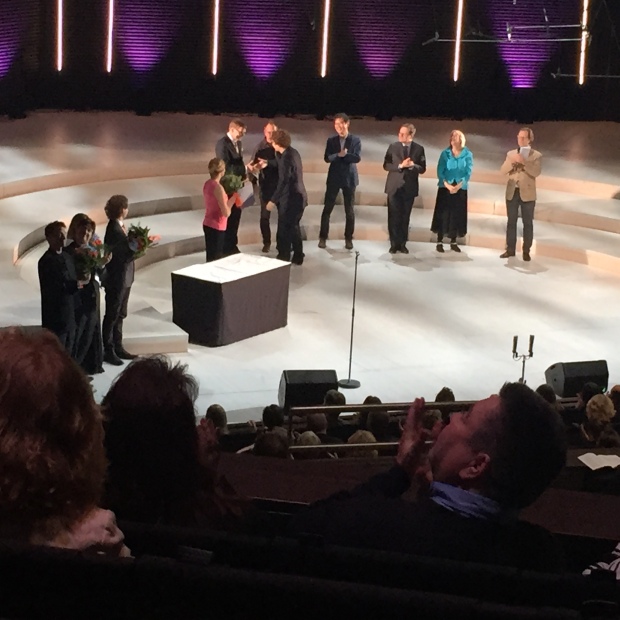

Helsinki At the Harald Anderson Chamber Choir Competition, I’m glad I’m not judging, because I can’t tell who’s winning.

The choruses came from all over–Estonia, Latvia, Sweden, Ireland. One of the four Finnish finalist choirs has arrayed itself all over the hall, and they’re coherent, on the beat, wired together. They’re singing with emotion, but they’re also predicting the future, so as to keep in synchrony, their auditory and motor cortices teaming up to compute the arrival of the next beat.

We Homos think we’re so visual, but everything comes down to timing. Forget our precious eyes. The ears have it. Neuro-philosophes love to ask, which came first, music or words? If you ask a book, it’ll say in the beginning was the word. And the songwriter says it’s the contract. One theory says that to keep the beat, you have to have a brain capable of speech. So if you want to jam with someone from another species, try a cockatoo. They got rhythm:

But sea lions don’t have much vocabulary, and they’re dancing machines:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s4nBevZJMvk

Did you ever wonder why your dog won’t dance? It’s because she can’t. She can sing rubato till the cows come home, but she can’t dance to save her soul. And don’t ask me why it takes so long to teach chimpanzees to tap along with a rhythm. Even at their best, their timing is all over the place. They just don’t have it.

My trip is over; it’s been just a short journey towards the future, and I’m bringing it back home. There’s a massive orchestra of maple trees, synchronized colors, waiting. Then, come June, I’ll hear that ever-loving buzz of fireflies, and hum along to their neon beat.

The theme of my talk was obvious enough: this musical toy makes sense, because children, like other human beings, use music as an emotional prosthesis, a technology of the self.

The theme of my talk was obvious enough: this musical toy makes sense, because children, like other human beings, use music as an emotional prosthesis, a technology of the self.

I look up and through the air they’ve flown, site of the rescue of their prize, their queen. Whether I’m annoyed at the silence, or I just miss their company, I can’t tell. My son is looking down at me from the barn foundation wall. “They doing okay in there?” “They’re gone … hopefully they’ve got another story.”

I look up and through the air they’ve flown, site of the rescue of their prize, their queen. Whether I’m annoyed at the silence, or I just miss their company, I can’t tell. My son is looking down at me from the barn foundation wall. “They doing okay in there?” “They’re gone … hopefully they’ve got another story.”